Corridoi Umanitari - Humanitarian Corridors: New Solutions for Refugee Safety and Integration

Pope Francis views the humanitarian corridor initiative as a drop that can change the sea and the world. When facing the humanitarian and refugee crisis due to the Syrian conflict he went to the island of Lesbos and took 12 with him. In the press conference on the return trip, when asked why he had gone for only 12 people, he replied by citing a similar question a reporter had asked Mother Teresa: “So much effort, so much work, just to help people die? What she does is useless! The sea is so big! ”. And she replied: "It is a drop of water in the sea, but after this drop the sea will not be the same!". And so the Pope echoes: “It is a small gesture. But of those small gestures that we all have to do to reach out to those in need." A drop that can change the sea

The Need for Safe Passages

During the 2022 Academic Global Immersion #AGIROME Program, the students felt emotionally drained. On one hand we met nonprofit and international organizations scrambling to respond to the rapidly escalating Ukrainian humanitarian crisis that emerged over the ongoing global humanitarian crises with more than 82 million of forcibly displaced people around the world. On the other hand, we heard heartbreaking testimonies of refugees who had to endure terrible journeys to escape war, violence and discrimination in their countries and to reach safety and seeking humanitarian protection in Europe. Many of them had friends that drowned in the Mediterranean Sea, others that were kidnapped to extort more money from their families, and some of them were left abandoned by smugglers in the desert, arrested by corrupted police, or raped and got pregnant during the months long - sometimes years long, traumatic journeys.

Pope Francis welcomes a group of Syrian refugees after they landed at Ciampino airport in Rome, following a visit at the Moria refugee camp in the Greek island of Lesbos, April 16, 2016. (RNS/AP/Filippo Monteforte) NCRInnovative Solution for Humanitarian Protection

It was in the midst of these stories, testimonies and recollection of the incredible work of these nonprofit, civil society and humanitarian agencies that we learn about the Corridoi Umanitari - Humanitarian Corridors Initiative which started with Pope Francis in 2016. "When Pope Francis’s travelled to Lesbos in April 2016, he brought back with him three Syrian families to Italy that the Holy See then provided accommodation and support for, while the Comunità di Sant’Egidio was put in charge of their integration. In May 2019, the pope said that he wanted to something similar a gain for families from Afghanistan, Cameroon and Togo (Onuitalia, 2019).

Entry posters at the Conference on Humanitarian and University Corridors organized by University of San Francisco's AGIROME program and hosted by Loyola University Chicago's JFC in Rome. The even was coordinated by Dr. Chiara Peri and included the participation of UNHCR, CARITAS and FCEI. Source: USFCA-AGIROMECivil Society Organizations Solutions

The Community of Sant'Egidio, in partnership with the Waldensian Evangelical Church (Tavola Valdese della Chiesa Evangelica Valdese, CEV), the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy (FCEI), Conferenza Episcopale Italiana - Caritas Italiana and in accordance with the dispositions of the Italian authorities (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Interior) along the support of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR-Italy), have created these innovative solutions for safe passage and integration. The Humanitarian Corridor initiative along its other connected programs for university corridors (UNICORE), represents what Pope Francis called "A drop that can change the sea." (Farnesina).

Dr. Marco Impagliazzo, President of the Community of Sant'Egidio personally welcoming refugees arriving in Italy through the Humanitarian Corridors initiative. "We said: how can we avoid the deaths of thousands of people, including children, in the Mediterranean Sea? The answer was: let's open Humanitarian Corridors for Refugee, a completely self-financed project implemented by the Community of Sant'Egidio with the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy and the Tavola Valdese (Sant'Egidio).Reducing Risks with Safe Passages

"The fact that many of these refugees are unable to legally access effective international protection, shows the weakness of the system European legislation and national policies, unable to protect people more vulnerable. Potential asylum seekers having limited possibilities reception and protection in transit countries located in the Middle East, Corn of Africa and North Africa, however, already overwhelmed by the presence of a large number of refugees, see Europe as the only viable alternative, albeit in a way irregular. These people are, therefore, forced to save themselves undertaking dangerous journeys and relying on human traffickers for a fee exorbitant figures and experiencing very high risk situations." (Translation from Caritas Italian (2019) Oltre il Mare: Primo rapporto sui Corridoi Umanitari in Italia e altre vie legali e sicure d’ingresso).

Maria Quinto, Humanitarian Corridors coordinator for the Community of Sant’Egidio, (centre) with Hebat, aged nine, from Syria, just after she landed in Rome from Lebanon. © UNHCR/Alessandro Penso (UNHCR).Humanitarian Corridors Solutions

The Humanitarian Corridor initiative foresees that the civil society organizations identify in the country of first asylum, refugees or persons in need of international protection with serious vulnerabilities to be legally transferred to Italy, where they are received by the same organizations and supported by them in the integration process. [...]. Once in Italy, the people selected by the associations apply for asylum to the Italian authorities, to be recognized as refugees. In the meantime, the beneficiaries of the project are housed in accommodation managed by the organizations, which take care of their sustenance and integration process" (UNHCR-It)

University Humanitarian Corridors: A group of 37 refugees arrived in Italy last week as part of the UNICORE - University Corridors for Refugees project. Thanks to scholarships, they will continue their studies at 23 universities in the country. From file: UNHCR and Caritas workers offering assistance to refugees arriving via a humanitarian corridor at the Fiumicino airport | Photo:ARCHIVE/ANSA/TELENEWSUNICORE - University Humanitarian Corridors

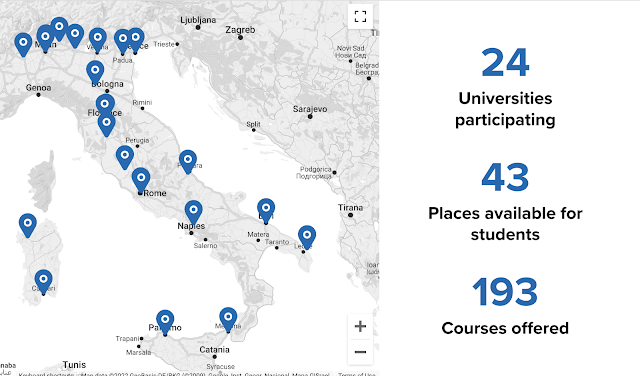

The project UNICORE, currently in its third year, offers safe passage and integration through university corridors and scholarship opportunities for young people in vulnerable contexts. "The project University Corridors for Refugees UNICORE 3.0 is promoted by 24 Italian universities with the support of UNHCR, Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Caritas Italiana, Diaconia Valdese, Centro Astalli and other partners. It aims to increase opportunities for refugees currently residing in Ethiopia to continue their higher education in Italy." (UNICORE 3.0).

A Long and Difficult History of Humanitarian Corridors

The Corridoi Umanitari - humanitarian corridors are a new attempt from civil society (nonprofit, associations, NGOs, etc.) to respond to the humanitarian crisis in times of conflicts. We hear these days quote often this word "humanitarian corridors" as the International Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations scramble to bring civilians to safety from Ukraine while also assisting with food and medicine. In spite the fact these fundamental rights of "rapid and unimpeded passage” have been adopted in the 1949 Geneva Conventions (for civilians, food, clothing, medicine) and in the 1990 United Nations resolutions recognizing humanitarian corridors (for humanitarian operators), these "safe" passages have been continuously violated or abused as in the case of Syria or Bosnia. I personally remember when we were attached during the humanitarian operations I took part in 1992-1993 (Mir Sada - Peace Now) bringing medicines and food to the sieged people of Sarajevo during the Bosnian war. Later in 1995, the “safe areas” established in the town of Srebrenica became the worst mass murder in Europe since World War II when at least 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were killed (WAPO, 2022).

Catholic and Protestant communities call for humanitarian corridors: "The need to protect human rights and founding values of the Western society, such as democracy, freedom of expression and education, has been called for by the religious communities, but it is challenged by the political polarization that the issue of migration has taken on in Europe." (ONUITALIA).Pope Francis for Ukrainian Humanitarian Corridors

The Vatican has been reporting on Pope Francis's many heartfelt plea for peace in Ukraine, guaranteed humanitarian corridors, and for all people to come to the assistance of the war victims, especially the mothers and children fleeing.

"Rivers of blood and tears are flowing in Ukraine" said Pope Francis. "I make a heartfelt appeal for humanitarian corridors to be genuinely secured, and for aid to be guaranteed and access facilitated to the besieged areas, in order to offer vital relief to our brothers and sisters oppressed by bombs and fear. I thank all those who are taking in refugees. Above all, I implore that the armed attacks cease and that negotiation - and common sense - prevail. And that international law be respected once again!" (Vatican News).

Learn more on Humanitarian Corridors

- FCEI, Sant'Egidio, Chiesa Valdese (2016). How do humanitarian corridors work? An Italian ecumenical project signals hope for Europe

- Sant'Egidio (2019). HUMANITARIAN CORRIDORS in Europe. Dossier: Humanitarian Corridors in Italy, France, Belgium and Andorra, the Principality of Monaco.

- Working Group of the Humanitarian Corridors Project. Humanitarian Corridors: implementation procedures for their extension on a European scale.

- Gois, P. & Falchi, G. (2017). THE THIRD WAY. HUMANITARIAN CORRIDORS IN PEACETIME AS A (LOCAL) CIVIL SOCIETY RESPONSE TO A EU’S COMMON FAILURE. REMHU, Rev. Interdiscip. Mobil. Hum., Brasília, v. 25, n. 51, dez. 2017, p. 59-75.

- Panchetti, & Wartensee. (2020). THE HUMANITARIAN CORRIDORS EXPERIENCE. ResearchGate.

.jpg)